Chapter 12 Building good visualizations

Visualization should nearly always be the first step in analyzing simulation results. In the prior chapter, we saw a series of visualizations that showed overall trends across a variety of examples. Those visualizations were not the initial ones created for those research projects. In practice, making a visualization often requires creating a bunch of graphs to look at different aspects of the data. From that pile of graphs, you would then refine ones that communicate the overall results most cleanly, and include those in your main write-up.

In our work, we find we often generate a series of R Markdown reports with comprehensive simulation results targeting our various research questions. These initial documents are then discussed internally by the research team.

In this chapter we discuss a set of common tools that we frequently use to explore our simulation results. In particular, we focus on four essential tools:

- Subsetting: Multifactor simulations can be complex and confusing. Sometimes it is easier to first explore a subset of the simulation results, such as a single factor level.

- Many small multiples: Plot many results in a single plot, with facets to break up the results by simulation factors.

- Bundling: Group the results by a primary factor of interest, and then plotting the performance measure as a boxplot so you can see how much variation there is within that factor level.

- Aggregation: Average the performance measure across some of the simulation factors, so you can see overall trends.

To illustrate these tools, we walk through them using our running example of comparing methods for analyzing a Cluster RCT. We will start with an investigation of bias.

As a reminder, in our Cluster RCT example, we have three methods for estimating the average treatment effect: linear regression of the student-level outcome onto treatment (with cluster-robust standard errors); aggregation, where we regress the cluster-level average outcome onto treatment (with heteroskedastic robust standard errors); and multilevel modeling with random effects.

We want to know if these methods are biased for our defined estimand, which is the cluster-average effect.

We have five simulation factors: school size (n_bar), number of schools (J), the intraclass correlation (ICC), the degree of variation in school size (alpha), and the relationship between school size and treatment effect (size_coef).

Once we go through the core tools, we continue our evaluation of our simulation to show how we can assess various performance metrics of interest (true standard error, RMSE, estimated standard errors, and coverage) using these tools. We do not dive deeply into validity or power; see Chapter 20 for more on these measures.

12.1 Subsetting and Many Small Multiples

As an initial exploration, you can simply filter the simulation results to a single factor level for some nuisance parameter. Generally, with small multiples, it is relatively straightforward to look at three simulation factors. This is because, with a facet grid, you can plot five things easily: two for the facets, one for the x-axis, one for color/line type, and one for the y-axis. We usually use two of these for method and outcome, giving three factors to explore.

For example, for our simulation, we might examine an ICC of 0.20 only, taking it as a “reasonable” value that, given our substance matter knowledge, we know is frequently found in empirical data.

We might further pick \(\bar{n} = 80\), as our middle level for that factor.

This leaves three factors, allowing us to plot all of our simulation results.

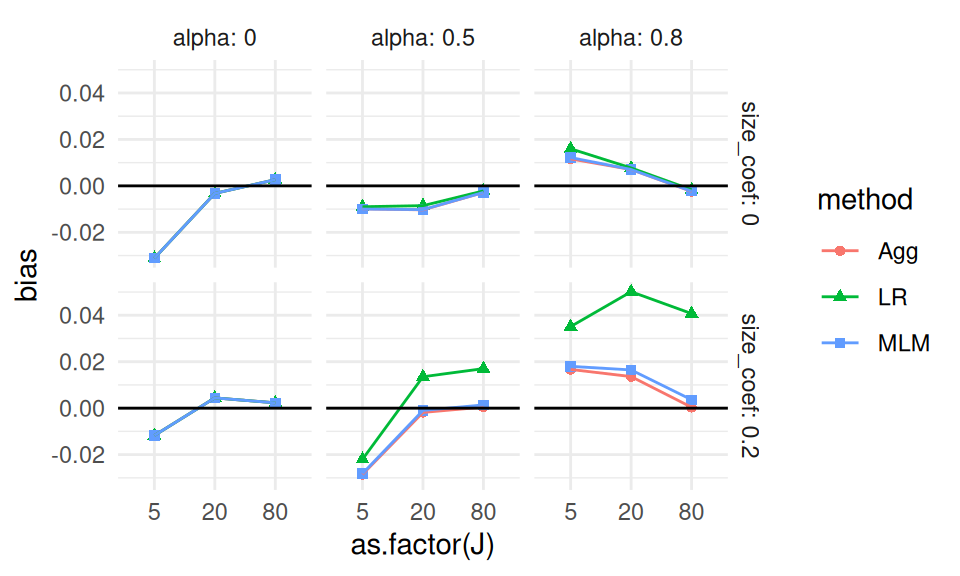

We plot bias as a function of J, with different lines for the different methods, and facets for the different levels of size_coef and alpha.

sres_sub <- sres %>%

filter( ICC == 0.20, n_bar == 80 )

ggplot( sres_sub, aes( as.factor(J), bias,

col=method, pch=method, group=method ) ) +

facet_grid( size_coef ~ alpha, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_point() + geom_line() +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0 ) +

theme_minimal()

Each point is one of our methods in one of our simulation scenarios. We are looking at the raw results. We connect the points with lines to help us see trends within each of the small multiples. The lines help us visually track which group of points goes with which.

We immediately see that when there is a lot of site variation, and it relates to outcome, linear regression is very different from the other two methods.

We also see that when alpha is 0 and size_coef is 0, we may also have a negative bias.

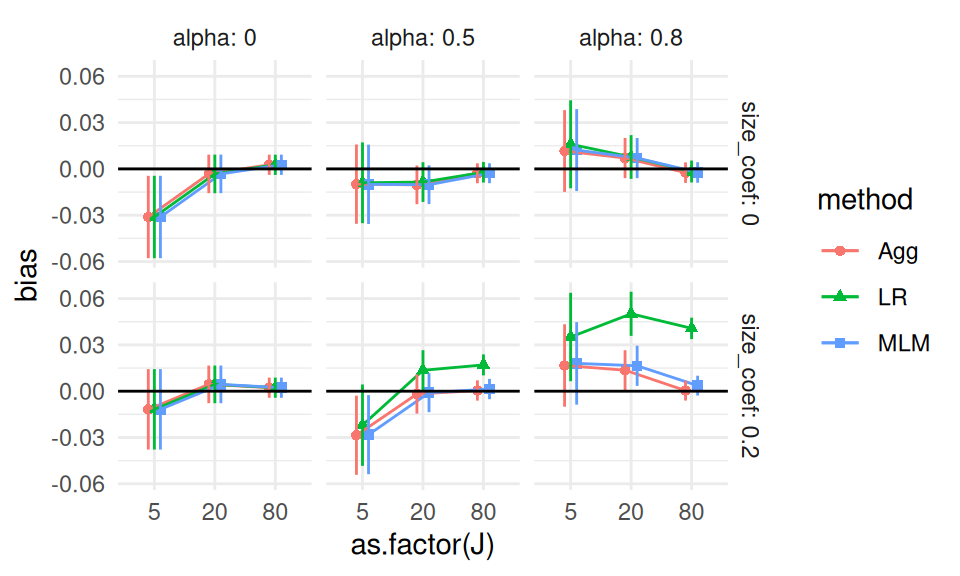

Before we get too excited about this surprising result, we calculate MCSEs to see if this is a real effect or just noise:

ggplot( sres_sub, aes( as.factor(J), bias,

col=method, pch=method, group=method ) ) +

facet_grid( size_coef ~ alpha, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_point( position = position_dodge( width=0.3) ) +

geom_line(position = position_dodge( width=0.3)) +

geom_errorbar( aes( ymin = bias - 1.96*bias_mcse,

ymax = bias + 1.96*bias_mcse ),

position = position_dodge( width=0.3),

width = 0 ) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0 ) +

theme_minimal()

Our confidence intervals exclude zero!

Our excitement mounts.

We next check all the scenarios with alpha = 0, and size_coef = 0 to see if this is a real effect.

We can still plot all our data, as we only have three factors, ICC, J_bar, and n_bar, left to plot.

null_sub <- sres %>%

dplyr::filter( alpha == 0, size_coef == 0 )

ggplot( null_sub, aes( ICC, bias,

col=method, pch=method, group=method ) ) +

facet_grid( J ~ n_bar, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_point( position = position_dodge( width=0.03) ) +

geom_line( position = position_dodge( width=0.03) ) +

geom_errorbar( aes( ymin = bias - 1.96*bias_mcse,

ymax = bias + 1.96*bias_mcse ),

position = position_dodge( width=0.03),

width = 0 ) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0 ) +

theme_minimal()

It appears that our ICC=0.20 and n_bar=80 scenario was just a fluke.

Almost everything else easily covers 0, and we are not seeing any major trends.

Overall we conclude that indeed, when there is no variation, or when the variation does not relate to impact, nothing is particularly biased.

Interestingly, we further see that all methods seem to give identical estimates when there is no site variation, regardless of ICC, J, or n_bar (that is the easiest explanation of all the estimated biases and associated MCSEs being identical).

Subsetting is a very useful tool, especially when the scope of the simulation feels overwhelming. And as we just saw, it can also be used as a quick validity check: we can subset to a known context where we know nothing exciting should be happening, and then check that indeed nothing is there.

Subsetting allows for a deep dive into a specific context. It also can make it easier to think through what is happening in a complex context. Sometimes we might even just report a subset in our final analysis. In this case, we would consider the other levels as a “sensitivity” analysis vaguely alluded to in our main report and placed elsewhere, such as an online supplemental appendix.

It would be our job, in this case, to verify that our reported findings on the main results indeed were echoed in our other, set-aside, simulation runs. In our case, as we see below, we will see little effect of the ICC on how one model performs relative to another; we thus might be able to safely ignore the ICC factor in our main report.

Subsetting is useful, but if you do want to look at all your simulation results at once, you need to somehow aggregate your results to make them all fit on the plot. We next present bundling, a way of using the core idea of small multiples for showing all of the raw results, but in a semi-aggregated way.

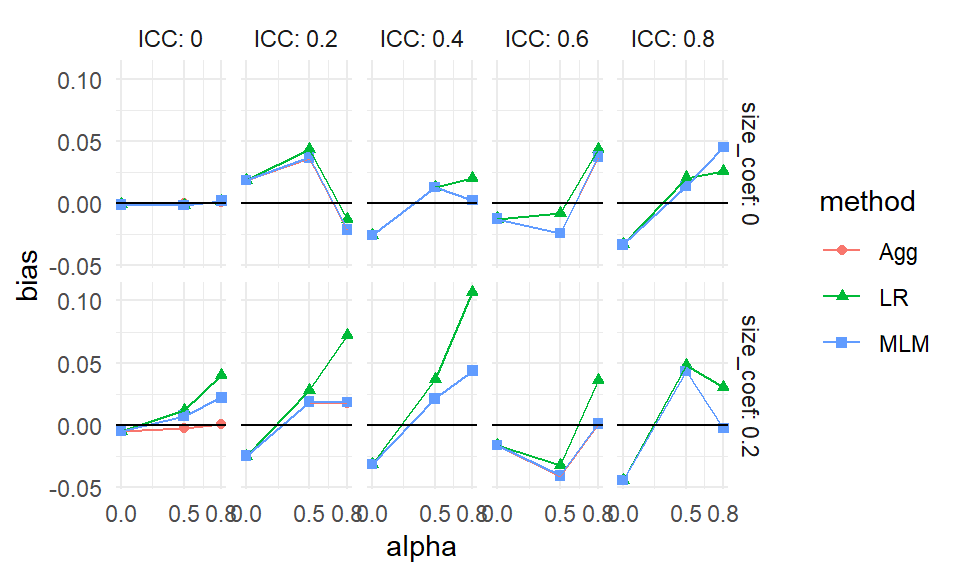

12.2 Bundling

When faced with many simulation factors, we can bundle the simulations into groups defined by a selected primary factor of interest, and then plot each bundle with a boxplot of the distribution of a selected performance criteria. Each boxplot shows the central measure of how well an estimator worked across a set of scenarios, along with a sense of how much that performance varied across those scenarios. If the boxes are narrow, then we know that the variation across simulations within the box did not impact performance much. If the boxes are wide, then we know that the factors that vary within the box matter a lot for performance.

With bundling, we generally need a good number of simulation runs per scenario, so that the MCSE in the performance measures does not make our boxplots look substantially more variable (wider) than the truth. (Consider a case where all the scenarios within a box have zero bias; if MCSE were large, we would see a wide boxplot when we should not.)

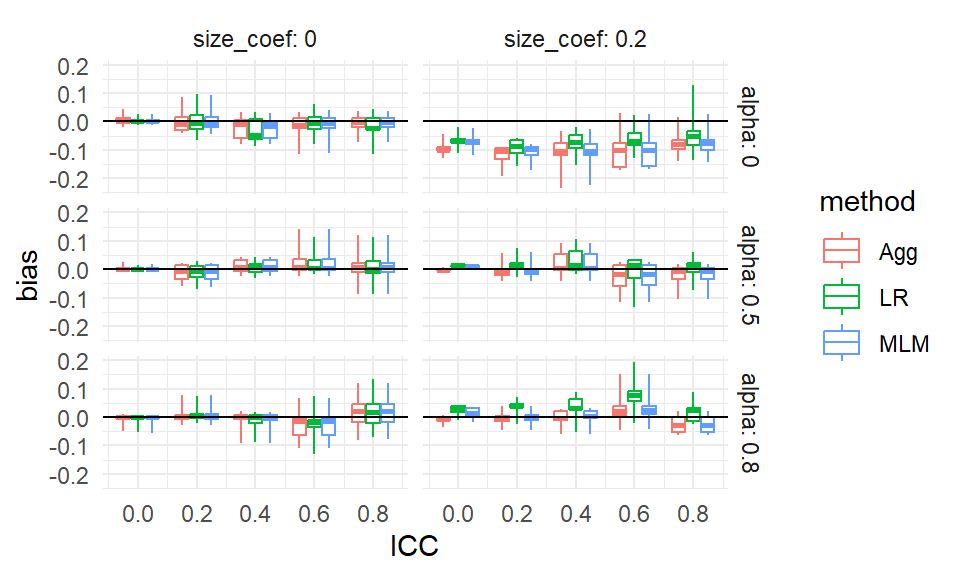

To illustrate bundling, we group our Cluster RCT results by method, ICC, the size coefficient (how strong the cluster size to treatment impact relationship is), and alpha (how much the cluster sizes vary). For a specific ICC, size, and alpha, we will put the boxes for the three methods side-by-side to directly compare them:

ggplot( sres, aes( as.factor(alpha), bias, col=method, group=paste0(ICC,method) ) ) +

facet_grid( size_coef ~ ICC, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_boxplot(coef = Inf) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0 ) +

theme_minimal()

Each box is a collection of simulation trials. E.g., for ICC = 0.6, size_coef = 0.2, and alpha = 0.8 each of the three boxes contains 9 scenarios representing the varying level 1 and level 2 sample sizes.

Here are the 9 for the Aggregation method:

filter( sres,

ICC == 0.6,

size_coef == 0.2,

alpha == 0.8, method=="Agg" ) %>%

dplyr::select( n_bar:alpha, bias ) %>%

knitr::kable( digits = 2 )| n_bar | J | ATE | size_coef | ICC | alpha | bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.04 |

| 20 | 20 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.02 |

| 20 | 80 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | -0.01 |

| 80 | 5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | -0.02 |

| 80 | 20 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.02 |

| 80 | 80 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.00 |

| 320 | 5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.01 |

| 320 | 20 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.01 |

| 320 | 80 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.01 |

Our bias boxplot makes some trends clear. For example, we see that there is virtually no bias for any method when the size coefficient is 0 and the ICC is 0. It is a bit more unclear, but it seems there is also virtually no bias when the size coefficient is 0 regardless of ICC, but the boxes get wider as ICC increases, making us wonder if something else is potentially going on. When alpha is 0 and the size coefficient is 0.2, all methods have a negative bias for most scenarios considered, as all boxes and almost all of the whiskers are below the 0 line (when ICC is 0.6 or 0.8 we may have some instances of 0 or positive bias, if that is not MCSE giving long tails).

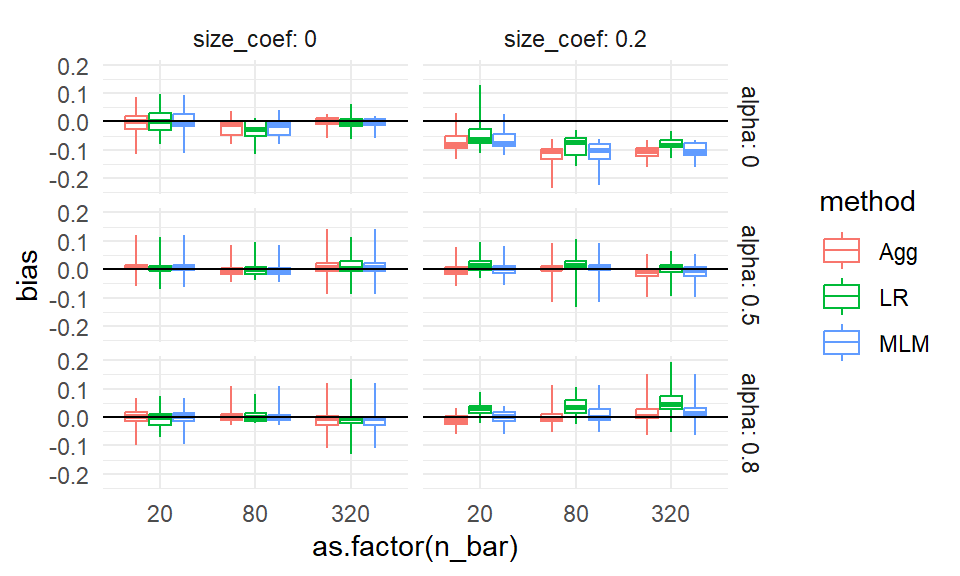

The apparent outliers (long tails) for some of the boxplots suggest that the other two factors (cluster size and number of clusters) do relate to the degree of bias. We could try bundling along different aspects to see if that explains these differences:

ggplot( sres, aes( as.factor(n_bar), bias, col=method, group=paste0(n_bar,method) ) ) +

facet_grid( alpha ~ size_coef, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_boxplot(coef = Inf) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0 ) +

theme_minimal()

No progress there; we have long tails suggesting something is allowing for large bias in some contexts. This could be MCSE, with some of our bias estimates being large due to random chance. Or it could be some specific combination of factors allows for large bias (e.g., perhaps small sample sizes makes our estimators more vulnerable to bias). In an actual analysis, we would make a note to investigate these anomalies later on.

In general, playing around with factors so that the boxes are generally narrow is a good idea; it means that you have found a representation of the data where the variation within your bundles is less important. This might not always be possible, if all your factors matter; in this case the width of your boxes tells you to what extent the bundled factors matter relative to the factors explicitly present in your plot.

12.3 Aggregation

Boxplots can make seeing trends more difficult, as the eye is drawn to the boxes and tails, and the range of your plot axes can be large due to needing to accommodate the full tails and outliers of your results; this can compress the mean differences between groups, making them look small. Instead of bundling, we can therefore aggregate, where we average all the scenarios within a box to get a single number of average performance. This will show us overall trends rather than individual simulation variation.

When we aggregate, and average over some of the factors, we collapse our simulation results down to fewer moving parts. Aggregation across factors is better than not having varied those factors in the first place! A performance measure averaged over a factor is a more general answer of how things work in practice than having not varied the factor at all.

For example, if we average across ICC and site variation, and see that our methods had different degrees of bias as a function of \(J\), we would know that the found trend is a general trend across a range of scenarios defined by different ICC and site variation levels, rather than a specific one tied to a single ICC and amount of site variation. Our conclusions would then be more general: if we had not explored more scenarios, we would not have any sense of how general our found trend might be.

That said, if some of our scenarios had no bias, and some had large bias, when we aggregated we would report that there is generally a moderate amount of bias. This would not be entirely faithful to the actual results. If, however, the initial boxplots show results generally in one direction or another, then aggregation will be more faithful to the spirit of the results.

Also, aggregated results can be misleading if you have scaling issues or extreme outliers. With bias, our scale is fairly well set, so we are good. But if we were aggregating standard errors over different sample sizes, then the larger standard errors of the smaller sample size simulations (and the greater variability in estimating those standard errors) would swamp the standard errors of the larger sample sizes. Usually, with aggregation, we want to average over something we believe does not change massively over the marginalized-out factors. To achieve this, we can often average over a relative measure (such as standard error divided by the standard error of some baseline method), which tend to be more invariant and comparable across scenarios.

A major advantage of aggregation over the bundling approach is we can have fewer replications per scenario. If the number of replicates within each scenario is small, then the performance measures for each scenario is estimated with a lot of error; the aggregate, by contrast, will be an average across many more replicates and thus give a good sense of average performance. The averaging, in effect, gives a lot more replications per aggregated performance measure.

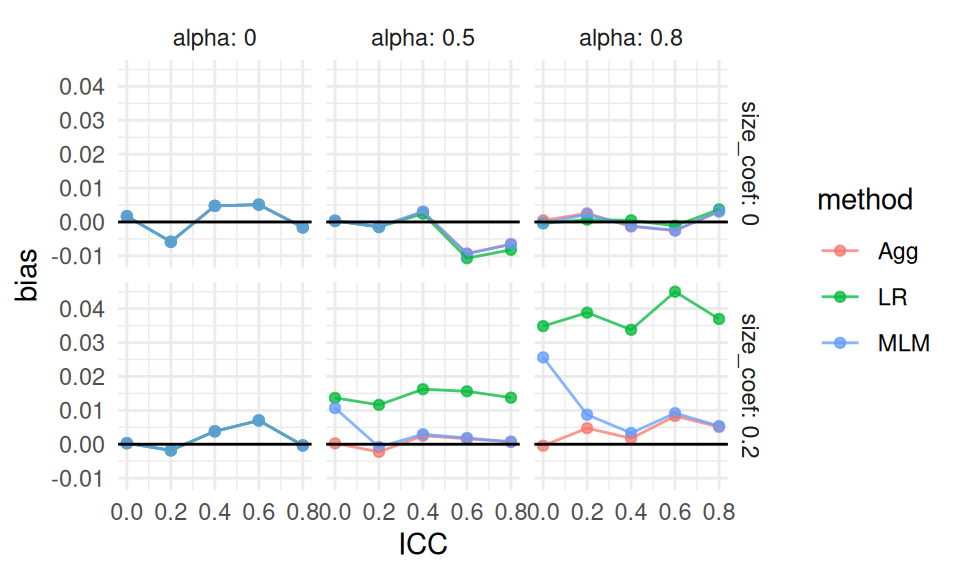

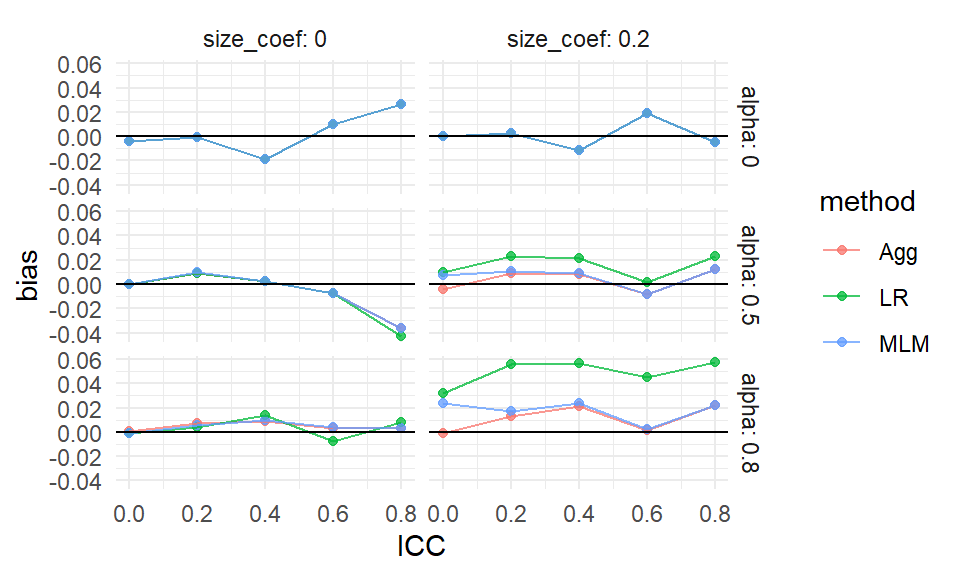

For our cluster RCT, we might aggregate our bias across our sample sizes as follows:

ssres <-

sres %>%

group_by( method, ICC, alpha, size_coef ) %>%

summarise( bias = mean( bias ),

n = n() )We now have a single bias estimate for each combination of ICC, alpha, and size_coef; we have collapsed 9 scenarios into one overall scenario that generalizes bias across different sizes of experiment. We can then plot, using many small multiples:

ggplot( ssres, aes( ICC, bias, col=method ) ) +

facet_grid( size_coef ~ alpha, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_point( alpha=0.75 ) +

geom_line( alpha=0.75 ) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0 ) +

theme_minimal()

We see more clearly that greater variation in cluster size (alpha) leads to greater bias for the linear regression estimator, but only if the coefficient for size is nonzero (which makes sense given our theoretical understanding of the problem—if size is not related to treatment effect, it is hard to imagine how varying cluster sizes would cause much bias). We are looking at an interaction between our simulation factors: we only see bias for linear regression when cluster size relates to impact and there is variation in cluster size. As ICC increases, we are not seeing any major differences in the pattern of our results We also see that all the estimators have near zero bias when there is no variation in cluster size, with the overplotted lines on the top row of the figure.

If you have many levels of a factor, as we do with ICC, you can let ggplot aggregate directly by taking advantage of the smoothing options:

ggplot( sres, aes( ICC, bias, col=method ) ) +

facet_grid( alpha ~ size_coef, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_point( alpha=0.10,

position = position_dodge(width = 0.04) ) +

geom_smooth( se=FALSE ) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0 ) +

theme_minimal()

In the above, we let the original points show faintly as well, to give a sense of the variation across simulation trials.

12.3.0.1 A note on how to aggregate

Some performance measures are biased with respect to the Monte Carlo uncertainty. The estimated standard error, for example, is biased; the variance, by contrast, is not. The RMSE is biased, the MSE is not.

When aggregating, therefore, it is often best to aggregate the unbiased performance measures, and then calculate the biased ones from those. For example, to estimate aggregated standard error you might do the following:

agg_perf <- sres %>%

group_by( ICC, method, alpha, size_coef ) %>%

summarise( SE = sqrt( mean( SE^2 ) ) )Because bias is linear, you do not need to worry about the bias of the standard error. But if you are looking at the magnitude of bias (\(|bias|\)), then you can run into issues when the biases are close to zero, if they are measured noisily. In this case, looking at average bias, not average \(|bias|\), is safer.

12.4 Assessing true SEs

We just did a deep dive into bias.

Uncertainty (standard errors) is another primary performance criterion of interest.

As an initial exploration, we plot the standard error estimates from our Cluster RCT simulation, using smoothed lines to visualize trends. We use ggplot’s geom_smooth to aggregate over size_coef and alpha, which we leave out of the plot.

We include individual data points to visualize variation around the smoothed estimates:

ggplot( sres, aes( ICC, SE, col=method ) ) +

facet_grid( n_bar ~ J, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_jitter( height = 0, width = 0.05, alpha=0.5 ) +

geom_smooth( se=FALSE, alpha=0.5 ) +

theme_minimal()## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and

## formula = 'y ~ x'

We observe several broad trends in the standard error behavior. First, standard error increases with the intraclass correlation (ICC). This is as expected: greater similarity within clusters reduces the effective sample size. Second, standard error decreases as the number of clusters (J) increases, which reflects the benefit of having more independent units of analysis. In contrast, increasing the cluster size (n_bar) has relatively little effect on the standard error (the rows of our facets look about the same). Lastly, all methods show fairly similar levels of standard error overall.

While we can extract all of these from the figure, the figure is still not ideal for comparing our methods. The dominant influence of design features like ICC and sample size obscures our ability to detect meaningful differences between methods. In other words, even though SE changes across scenarios, it’s difficult to tell which method is actually performing better within each scenario.

We can also view the same information using boxplots, effectively “bundling” over the left-out dimensions.

We also put n_bar in our bundles because maybe it does not matter that much:

ggplot( sres, aes( ICC, SE, col=method, group=paste0( ICC, method ) ) ) +

facet_grid( . ~ J, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_boxplot( width = 0.2, coef = Inf) +

scale_x_continuous( breaks = unique( sres$ICC)) +

theme_minimal()

Our plots are still dominated by the strong effects of ICC and the number of clusters (J). When performance metrics like standard error vary systematically with design features, it becomes difficult to compare methods meaningfully across scenarios.

To address this, we shift our focus through standardization. Instead of noting that:

“All my SEs are getting smaller,”

we want to conclude that:

“Estimator 1 has systematically higher SEs than Estimator 2 across scenarios.”

Simulation results are often driven by broad design effects, which can obscure the specific methodological questions we care about. Standardizing helps bring those comparisons to the forefront. Let’s try that next.

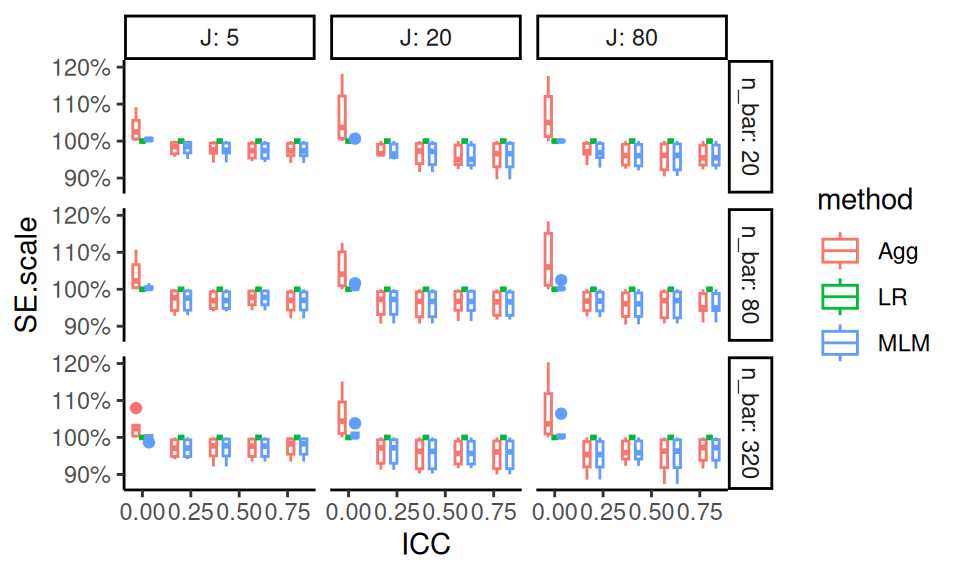

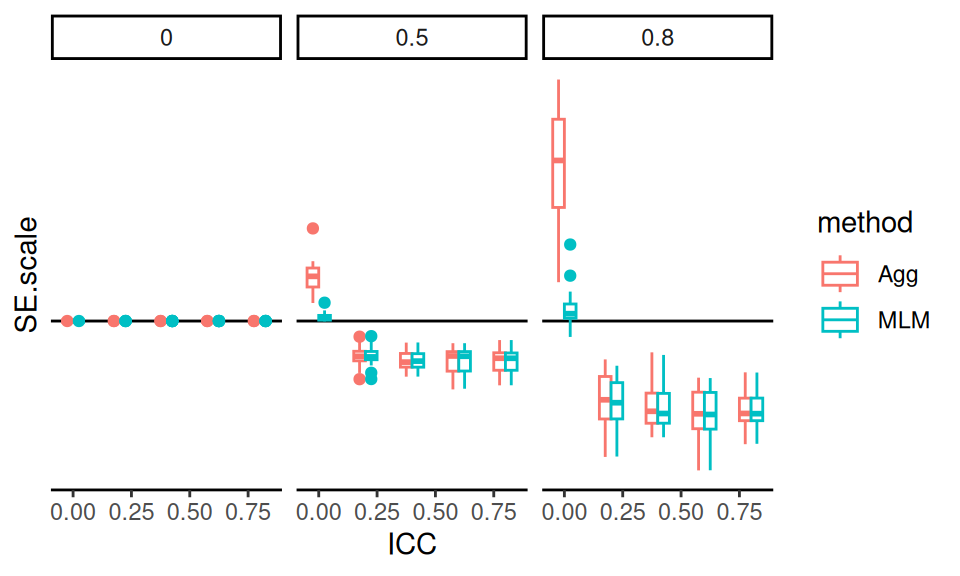

12.4.0.1 Standardizing to compare across simulation scenarios

One straightforward strategy for standardization is to compare each method’s performance to a designated baseline. In this example, we use Linear Regression (LR) as our baseline.

We focus on the standard error (SE) of each method’s estimate, rescaling it relative to LR.

We do this by, for each simulation scenario, dividing each method’s SE by the SE of LR, to produce SE.scale.

This relative measure, SE.scale, allows us to examine how much better or worse each method performs in terms of precision under varying conditions.

ssres <-

sres %>%

group_by( n_bar, J, ATE, size_coef, ICC, alpha ) %>%

mutate( SE.scale = SE / SE[method=="LR"]) %>%

ungroup()We can then treat it as a measure like any other. Here we bundle:

ggplot( ssres, aes( ICC, SE.scale, col=method,

group = interaction(ICC, method) ) ) +

facet_grid( n_bar ~ J, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_boxplot( position="dodge", width=0.1 ) +

scale_y_continuous( labels = scales::percent_format() )

The figure above shows how each method compares to LR across simulation scenarios. We see that Aggregation performs worse than LR when the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) is zero. However, when ICC is greater than zero, Aggregation yields improved precision. The Multilevel Model (MLM), in contrast, appears more adaptive. It captures the benefits of aggregation when ICC is high, but avoids the precision cost when ICC is zero. This adaptivity makes MLM appealing in practice when ICC is unknown or variable across contexts.

Although faceting by n_bar and J helps reveal potential interaction effects, it may be more effective to collapse across these variables for a cleaner summary. We are also not seeing how site size variation is impacting these results, and we might think that matters, especially for aggregation.

As a warning regarding Monte Carlo uncertainty: when standardizing results, it is important to remember that uncertainty in the baseline measure (here, LR) propagates to the standardized values. This should be considered when interpreting variability in the scaled results. Uncertaintly for relative performance is generally tricky to assess.

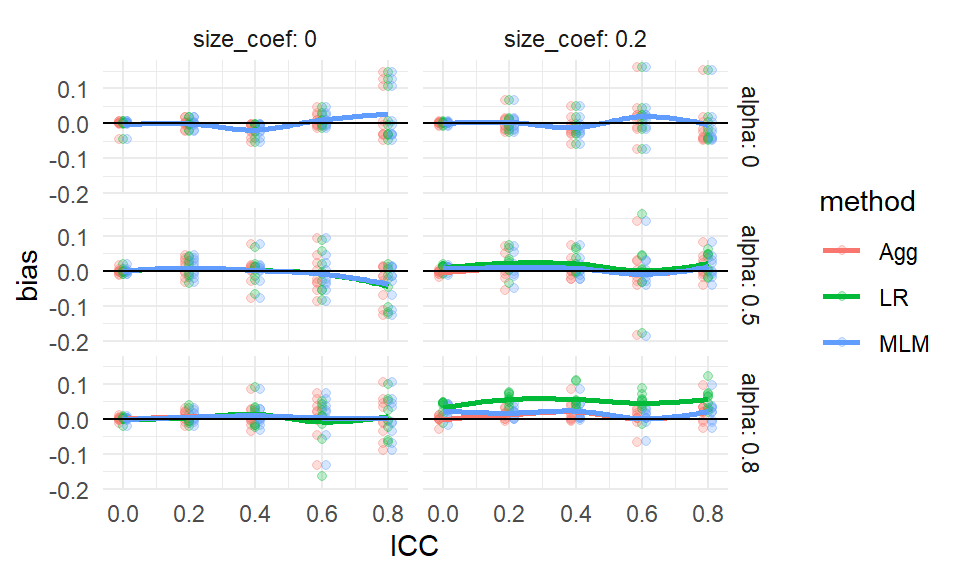

To clarify the main patterns, we average our SE.scale across simulation settings—relative performance is on the same scale, so averaging is a natural thing to do.

s2 <-

ssres %>%

group_by( ICC, alpha, method ) %>%

summarise( SE.scale = mean( SE.scale ) )

ggplot( s2, aes( ICC, SE.scale, col=method ) ) +

facet_wrap( ~ alpha ) +

geom_point() + geom_line() +

scale_y_continuous( labels = scales::percent_format() ) +

labs( title = "Average relative SE to Linear Regression",

y = "Relative Standard Error" )

Our aggregated plot of precision of aggregation and MLM relative to Linear Regression gives a simple story clearly told. The performance of aggregation improves with ICC. MLM also has benefits over LR, and does not pay much cost when ICC is low.

We can also visualize the variability in relative standard errors across simulation scenarios using boxplots. This allows us to examine how consistent each method’s performance is under different ICC conditions.

ssres %>%

filter( method != "LR" ) %>%

ggplot( aes( ICC, SE.scale, col=method,

group = interaction(ICC, method) ) ) +

facet_wrap( ~ alpha, nrow=1) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 1 ) +

geom_boxplot( position="dodge", width=0.1 ) +

scale_y_continuous( breaks=seq(90, 125, by=5 ) )

These boxplots show the full distribution of relative standard errors across all simulated scenarios, separated by ICC level. We exclude LR as it is the reference method.

The pattern is clear: when ICC = 0, Aggregation performs worse than LR, and MLM performs about the same. But as ICC increases, Aggregation and MLM both improve, and perform about the same to each other. This highlights the robustness of MLM across diverse conditions.

We might also explore how uncertainty changes with other factors. Here, we see whether cluster size meaningfully helps:

sres %>%

filter( alpha == 0.8, size_coef == 0.2 ) %>%

ggplot( aes( n_bar, SE, col=factor(ICC), group=ICC ) ) +

facet_grid( J ~ method, labeller = label_both, scales = "free") +

geom_point() + geom_line()

If the ICC is low, cluster size matters. Otherwise, the benefits are much more slim.

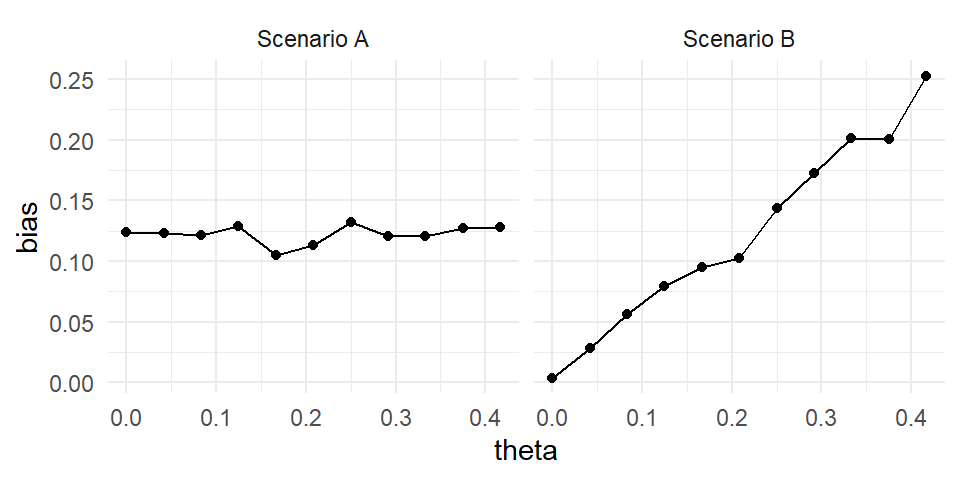

12.5 The Bias-SE-RMSE plot

We can also visualize bias and standard error together, along with RMSE, to get a fuller picture of performance. To illustrate, we subset to our biggest scenarios, in terms of sample size, and no ICC:

bsr <- sres %>%

filter( n_bar == 320, J==80, ICC == 0 )

bsr <- bsr %>%

dplyr::select( -R, -power, -ESE_hat, -SD_SE_hat ) %>%

pivot_longer( cols=c("bias","SE","RMSE"),

names_to = "measure",

values_to = "value" ) %>%

group_by( measure, size_coef, method, ICC, alpha ) %>%

summarise( value = mean( value ),

n = n() )

bsr$measure = factor( bsr$measure, levels=c("bias", "SE", "RMSE"),

labels =c("|bias|", "SE", "RMSE" ) )

ggplot( bsr, aes( alpha, value, col=method )) +

facet_grid( size_coef ~ measure ) +

geom_line() + geom_point() +

labs( y = "", x = "Site Variation" ) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0 ) +

theme( legend.position="bottom",

legend.direction="horizontal",

legend.key.width=unit(1,"cm"),

panel.border = element_blank() )

The combination of bias, standard error, and RMSE provides a rich and informative view of estimator performance.

As an illustration, in the above plot, we focus on a specific simulation scenario with n_bar = 320, J = 80, and ICC = 0. The top row represents settings where effect size is independent of cluster size, while the bottom row reflects a correlation between size and effect.

These types of visualizations directly illustrates the canonical relationship:

\[ \text{RMSE}^2 = \text{Bias}^2 + \text{SE}^2 \]

In the plot we get overall performance (RMSE) clearly decomposed into into its two fundamental components: systematic error (bias) and variability (standard error). Here we see how bias for LR, for example, is dominant when site variation is high. The differences in SE are small and so not the main reason for differences in overall estimator performance; bias is the main driver.

This is the kind of diagnostic plot we often wish were included in more applied simulation studies.

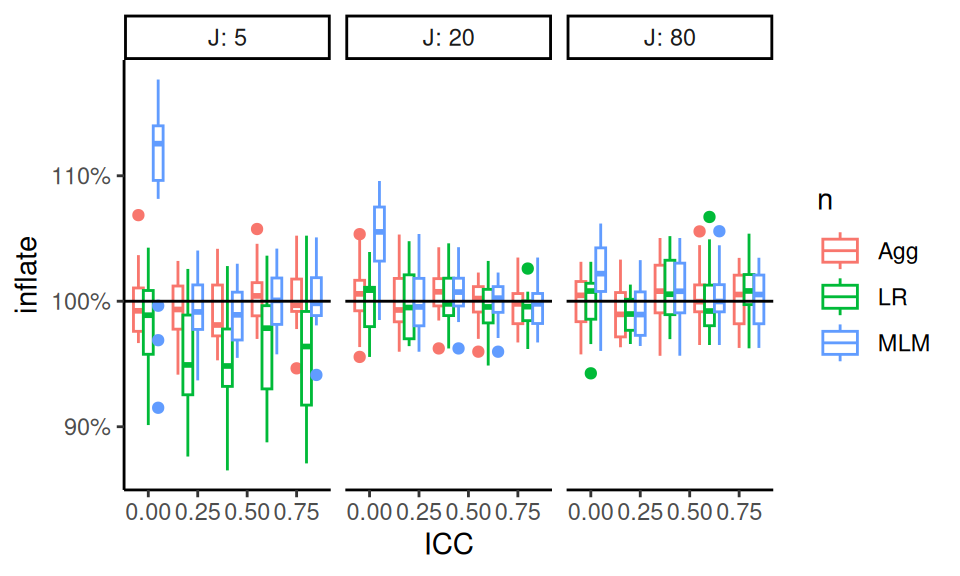

12.6 Assessing estimated SEs

So far we have examined the performance of our point estimators. We next look at ways to assess our estimated standard errors. A good first question is whether they are about the right size, on average, across all the scenarios.

Here it is very important to see if they are reliably the right size, so the bundling method is an especially important tool here. We first see if the average estimated SE, relative to the true SE, is usually around 1 across all scenarios:

sres <- sres %>%

mutate( inflate = ESE_hat / SE )

ggplot( sres,

aes( ICC, inflate, col=method,

group = interaction(ICC,method) ) ) +

facet_grid( . ~ J, labeller = label_both) +

geom_boxplot( position="dodge" ) +

geom_hline( yintercept=1 ) +

labs( color="n" ) +

scale_y_continuous( labels = scales::percent_format() )

We see that our estimated SEs are about right, on average, across all scenarios. When ICC is 0 and J is small, the MLM SEs are a bit too high. When J is 5, the LR estimator can be a bit low under some circumstances. We can start exploring these trends to dig into why our are wide (suggesting that other factors dictate when the SEs are biased).

We can look at the \(J = 80\) to see what MCSEs are like.

The simhelpers calc_relative_var() method gives mcses for relative bias.

se_res <- res %>%

group_by( n_bar, J, ATE, size_coef, ICC, alpha, method ) %>%

summarize( calc_relative_var( estimates = ATE_hat,

var_estimates = SE_hat^2,

criteria = "relative bias" ) )

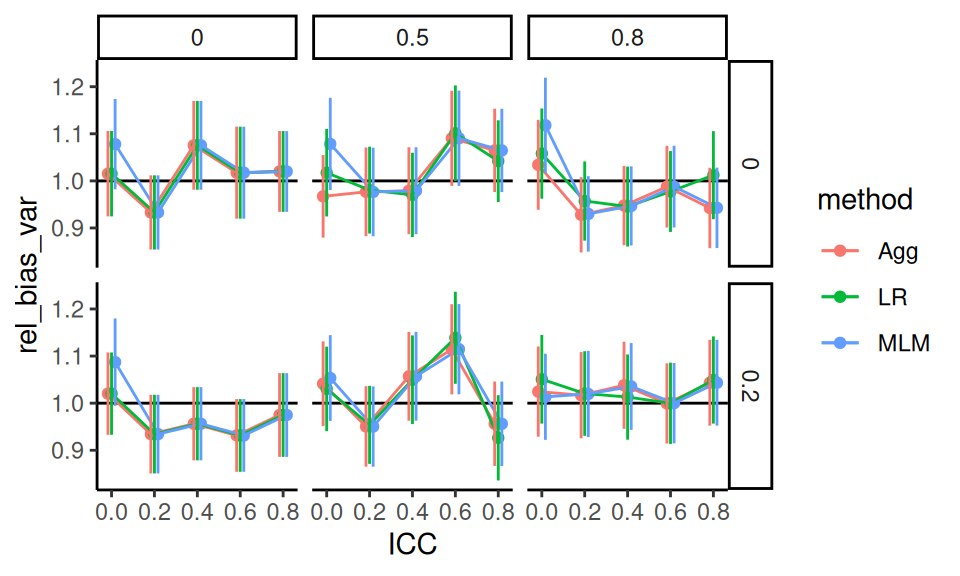

se_res %>%

filter( J == 80, n_bar == 80 ) %>%

ggplot( aes( ICC, rel_bias_var, col=method ) ) +

facet_grid( size_coef ~ alpha ) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 1 ) +

geom_point( position = position_dodge( width=0.05) ) +

geom_line( position = position_dodge( width=0.05) ) +

geom_errorbar( aes( ymin = rel_bias_var - 1.96*rel_bias_var_mcse,

ymax = rel_bias_var + 1.96*rel_bias_var_mcse ),

position = position_dodge( width=0.05 ),

width = 0 )

In looking at this plot, we see no real evidence of miscalibration. This makes us think the boxes in the prior plot are wide due to MCSE rather than other simulation factors driving some slight miscalibration in some scenarios when \(J\) is high. We might then assume this applies to the \(J = 20\) case as well.

Finally, we can look at how stable the estimated SEs are, relative to the actual uncertainty. We calculate the standard deviation of the estimated standard errors and compare that to the standard deviation of the point estimate.

sres <- mutate( sres,

SD_SE_hat_rat = SD_SE_hat / SE )

ggplot( sres,

aes( ICC, SD_SE_hat_rat, col=method,

group = interaction(ICC,method) ) ) +

facet_grid( . ~ J, labeller = label_both) +

geom_boxplot( position="dodge" ) +

labs( color="n" ) +

scale_y_continuous( labels = scales::percent_format() )

It looks like MLM has more reliably estimated SEs than other methods when ICC is small. Aggregation has more trouble estimating uncertainty when J is small. Finally, LR’s SEs are generally more unstable, relative to its performance, when \(J\) is larger.

Assessing the stability of standard errors is usually very in the weeds of a performance evaluation. It is a tricky measure: if the true SE is high for a method, then the relative instability will be lower, even if the absolute instability is the same. Thinking through what might be driving what can be difficult, and is often not central to the main purpose of an evaluation. People often look at confidence interval coverage and confidence interval width, instead, to assess the quality of estimated SEs.

12.7 Assessing confidence intervals

Coverage is a blend of how accurate our estimates are and how good our estimated SEs are.

To assess coverage, we first calculate confidence intervals using the estimated effect, estimated standard error, and degrees of freedom.

Once we have our calculated t-based intervals, we can average them across runs to get average width and coverage using simhelpers.

A good confidence interval estimator would be one which is generally relatively short while maintaining proper coverage.

Our calculations are as so:

res$df = res$J

res <- mutate( res,

tstar = qt( 0.975, df=df ),

CI_low = ATE_hat - tstar*SE_hat,

CI_high = ATE_hat + tstar*SE_hat,

width = CI_high - CI_low )

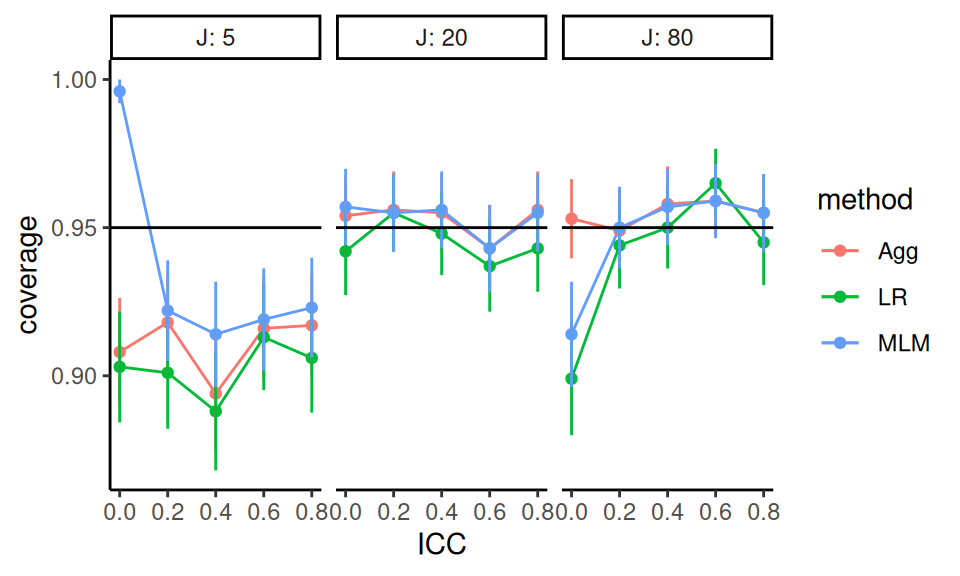

covres <- res %>%

group_by( n_bar, J, ICC, alpha, size_coef, method, ATE ) %>%

summarise( calc_coverage( lower_bound = CI_low,

upper_bound = CI_high,

true_param = ATE ) ) %>%

ungroup()We then look at those simulations with a relationship of site size and impact.

We subset to n_bar = 80, size_coef = 0.2 and alpha = 0.5 to simplify for our initial plot:

c_sub <- covres %>%

dplyr::filter( size_coef != 0, n_bar == 80, alpha == 0.5 )

ggplot( c_sub, aes( ICC, coverage, col=method, group=method ) ) +

facet_grid( . ~ J, labeller = label_both ) +

geom_line() +

geom_point() +

geom_errorbar( aes( ymax = coverage + 2*coverage_mcse,

ymin = coverage - 2*coverage_mcse ), width=0 ) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 0.95 )

Generally coverage is good unless \(J\) is low or ICC is 0. Monte Carlo standard errors indicate that, in some settings, the observed coverage is reliably different from the nominal 95%, suggesting issues with estimator bias, standard error estimation, or both. We might want to see if these results are general across other settings (see exercises).

For confidence interval width, we can calculate the average width relative to the width of LR across all scenarios:

covres <- covres %>%

group_by( n_bar, J, ICC, alpha, size_coef ) %>%

mutate( width_rel = width / width[method=="LR"] ) %>%

ungroup()

c_agg <- covres %>%

group_by( ICC, J, alpha, method ) %>%

summarise( coverage = mean( coverage ),

coverage_mcse = sqrt( mean( coverage_mcse^2 ) ) / n(),

width_rel = mean( width_rel ) ) %>%

filter( method != "LR" )

ggplot( c_agg, aes( ICC, width_rel, col=method, group=method ) ) +

facet_grid( J ~ alpha ) +

geom_hline( yintercept = 1 ) +

geom_line() + geom_point() +

labs( y = "Relative CI Width",

title = "Average Relative CI Width to Linear Regression" ) +

scale_y_continuous( labels = scales::percent_format() )

Confidence interval width serves as a proxy for precision. Narrow intervals suggest more precise estimates. We see MLM has wider intervals, relative to LR, when ICC is low. When there is site variation, both Agg and MLM have shorter intervals.

12.8 Exercises

12.8.1 Assessing uncertainty

Select a plot from this chapter that does not have monte carlo standard errors. Add monte carlo standard errors to that selected plot.

12.8.2 Assessing power

Make a plot showing how power changes as \(J\) changes. As an extra step, add MCSEs to the plot to assess whether you have a reasonable numbers of replications in the simulation.

12.8.3 Going deeper with coverage

For our cluster RCT, we saw coverage is low in some circumstances. Explore the full set of simulation results, possibly adding your own analyses, to ascertain why coverage is low. Is it due to estimator bias? Unreliably estimated standard errors? Something else? Make a final plot and draft a short write-up that captures how coverage is vulnerable for the three estimators.

12.8.4 Pearson correlations with a bivariate Poisson distribution

In Section 10.2, we generated results for a multifactor simulation of confidence intervals for Pearson’s correlation coefficient under a bivariate Poisson data-generating process. Create a plot that depicts the coverage rate of the confidence intervals for \(\rho\) across all four simulation factors. Write a brief explanation of how the plot is laid out and explain why you chose to construct it as you did.